|

The leaping bunny logo is synonymous with the cruelty-free cosmetics movement, starving polar bears are associated with the effects of anthropogenic climate change, and sea turtles growing up with deformed shells is a reminder of how plastic is ruining our oceans as a habitat for sea life. But when it comes to Fast Fashion, does the imagery of dead people come up when you’re about to pay for that $10 piece of clothing on sale? I suspect not, because human suffering doesn’t create emotional triggers for humans as much as animal suffering does. 2830 words; 14 mins read Updated 24 September 2018 For centuries, animals have been used in marketing, campaigning, and activism, because animals are strong emotional triggers and are effective at supporting a narrative. It’s no surprise that the use of imagery of animals in pain or suffering animals, partnered with clever context and messaging for Calls to Actions are effective in changing our attitudes. Graphic images, which are hard to ignore and impossible to forget, create an emotional connection to the issue it is promoting and raise ethical discussions. Just think about successful campaigns you’ve donated to or supported – carrying your own bags to the supermarket, boycott palm oil (orang utans and illegal destruction of their habitat), becoming vegan (cattle and their enormous greenhouse gas footprint), and not buying caged eggs (terrible farmed conditions for hens) – they all come from powerful imageries stuck in your mind. Coupled with other factors such as discussions with friends, watching documentaries and lifestyle shows, following in the footsteps of a celebrity you admire, and campaign actions from groups you subscribe to, it’s easy to empathise with the cause. I have been thinking about an easily identifiable mascot or symbol for the destructive Fast Fashion industry, but no animals came to mind. Truth be told, there already exists a mascot – underpaid garment workers. And worse – the deaths of underpaid, overused, unappreciated garment workers that worked for Fast Fashion. The Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh is nearing its fifth year anniversary, where Fast Fashion’s true colours came to the fore in mass media. TV outlets covered the deadliest garment industry accident in modern history, and Fashion Revolution, a not-for-profit organisation committed to enacting genuine change on worker rights and safety, was formed. The catastrophe injured nearly 2,600 and killed more than 1,138, including rescue workers. Animal mascots are effective, but humans not soTruth be told, there already exists a mascot – underpaid garment workers. And worse - the deaths of underpaid, overused, unappreciated garment workers... Some of the international brands implicated in the tragedy are Benetton (Italy), Bon Marche (UK), Cato Fashions (USA), The Children's Place (USA), El Corte Ingles (Spain), Joe Fresh (Loblaws, Canada), Kik (Germany), Mango (Spain), Matalan (UK), Primark (UK/Ireland) and Texman (Denmark.) The saddest thing about the tragedy was it was an avoidable one – but greed and political corruption were the order of the day instead of workers’ safety. It seems that the pain of experiencing a fatal workplace disaster doesn’t make us question ditching Fast Fashion enough. Let’s not forget also the survivors of the Rana disaster whom are now suffering long-term disabilities that make living in Bangladesh that much harder. Humans can’t relate to other humans as much as we’d like I conducted a quick poll with my friends on Facebook concerning the question of whether humans are more likely to empathise with animals or with other humans in relation to suffering and/or pain. Animals won (at the time of writing – 15 votes for animals; 10 for humans; 3 voted humans aren't capable of empathy for each other, let alone animals – *ouch*.) But let’s go back to science quickly. We all respond differently to imagery, whether still or moving. There are images that evoke positive emotional responses in the human brain. The most powerful are of:

Images of pain and suffering can most definitely elicit a commitment, a positive change from within an individual, or both. PETA’s (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals) controversial animal rights campaigns come into mind for example and even though they often receive mixed responses, some have been highly successful at shifting perceptions. Having said that, graphic imagery of animals being gassed for food production won’t necessary provoke or motivate an animal-free diet and can be a complete put off for some. Inversely, a healthy image of someone who has become vegan in recent years and posts colourful Instagram-worthy photos of their food evoke positive aspiration, and might just encourage you to take that leap of faith. The dehumanisation of our own species Even though some may remember what happened at Rana in 2013, we are quick to detach ourselves from its bigger social impacts. Throughout my thirty-five years of living I haven’t been immune to numerous human plights around the world. Even though my generation read about the great wars but never experienced them, crises around the world involving children, the sick and diseased, the treatment of workers in underdeveloped countries, battles waged against others due to differences in beliefs, and rebelling of governments due to corruption and atrocities still plague our news channels. Dehumanisation is the reason my Facebook poll result wasn’t kind towards human beings. Dehumanisation is viewed as a central component to intergroup violence because it is frequently the most important precursor to moral exclusion, the process by which stigmatised groups are placed outside the boundary in which moral values, rules, and considerations of fairness apply. David Livingstone Smith, director and founder of The Human Nature Project at the University of New England, argues that historically, human beings have been dehumanising one another for thousands of years. News stories on TV, print and online platforms perpetuate this state and perhaps we, as humans, have come to terms with the unpleasant side of the human race. We are desensitised to human plight, whether it be basic human rights, or on social justice issues, like what a fair wage looks like for a certain occupation. Our internal struggles for ethical consciousness Sometimes though, we are reminded of our innate human ability to connect with others. If I may, remember when images emerged of the lifeless body of three-year-old Alan Kurdi that washed up on a beach in Turkey in September 2015? It evoked a public response like no other, because here was an innocent and helpless child, a victim of adults dehumanising each other – in this case, the Syrian civil war had erupted four years earlier. Two-and-a-half years on, we had forgotten that that particular photograph shocked world leaders into action on the refugee crisis. And what about the media’s role in advancing ethics? Stories of little, or even big wins in the defence of the environment, fights for human rights, and government corruption crackdowns don’t get as much coverage in the mainstream news. It’s easy to conclude that one person, as in, YOU – can’t possibly play a role in the aftermath of Alan’s fate. I’m no psychologist, but this incapability to prevent Alan's death really does make us despise the human race most days! We can empathise with the stories of the refugees but can never fully understand it. (Unless you were born in a war-town country.) Stories of little, or even big wins in the defence of the environment, fights for human rights, and government corruption crackdowns don’t get as much coverage in the mainstream news. Humans are evilFor the one day that you are empowered enough to contribute to a cause and take action, there will be many more days where there are so many crises involving injustices in this world that seem out of reach and unsolvable for the average person. Let’s not kid ourselves. This feeling of powerlessness to enact change affects all of us, especially if we are not located anywhere near the crisis – regardless of whether you are a citizen of a First World Country (i.e. generally privileged) or not. In my case, Australia is so far from Europe. The best I could do was to lobby the government (through campaigns by Getup!, a not-for-profit movement and other similar organisations) to take in more Syrian refugees into the country – bar packing my bags, leaving my job and get on a plane headed to the Mediterranean to do something. I have likened this conflict of personal ethics to this realisation: It’s about what is feasibly under your sphere of influence, and what is not. International, different time-zone, another continent-type crises are too displaced for even our hearts to reach out to, and even though we love the thought of being ‘citizens of the world’ (for example, when it comes to holidays and vacations), we shy away from that notion when it comes to helping other people. We need break it down in human scale..There is a reasonable explanation for all this: distance. It is a significant barrier for even the most well-meaning of us, and time again we let the news stories run, we listen, and we get on with dinner. As someone who has worked in the environment sector all my career, I have also accepted the fact that the terms climate change and global warming are so damn unappealing. The reason why it is hard for people to relate to understanding how the climate works is because geologic time scales are long – too long for the human mind to really comprehend. “Over tens... and hundreds of millions of years, the Earth has changed from something unrecognisable to the planet we see on maps, plastic globes, and photos from space”, as Peter Gleick, internationally recognised climate and water expert, explains here. For a large percentage of the Earth’s age, there exists no USA, California, Australia, China, or Mount Everest. Humans cannot relate to these changes. Our perception of time is short – measured in days, months, years, or decades, not millennia or eons (Google it.) And our perception of the world around us is similarly driven by events with human time scales. It’s hard enough to think about what I’ll get up to this weekend, let alone how the planet will look like from outer space in two-hundred years. Heck, when I talk to my younger siblings about the importance of retirement savings, they laugh! Because they don’t think being sixty-five years old is even possible right now. One of the ways humans relate is symbols and mascots, something that represents a complex issue but conveyed at a level that is easy to grasp. In the fight against climate change, who can forget this heart-wrenching video that went viral of a polar bear clinging to life in Canada’s Baffin Islands? The thing is, all suffering is terrible. It’s now easy to see what transpired from my Facebook poll of human empathy towards animals. The emotive theory pretty much got decoded, in human scale. (Ooohhh……. snap!) For the one day that you are empowered enough to contribute to a cause and take action, there will be many more days where there are so many crises involving injustices in this world that seem out of reach and unsolvable for the average person. It’s not hard to relate. Let’s give this another go.This situation does not need to be completely discouraging, however. Remember the old adage, ‘Think Global, Act Local’? Yes! This is where YOU can be an agent of change. Every time you are faced with a problem that may seem impossible to tackle, I cannot stress how important it is that we don’t lose sight of the bigger picture. Snap yourself out of the ‘everything is too hard basket’ and re-wire your perspective. Contribute to the issue from your own sphere of influence! Because, believe me, every single human (human animal and non-human animal) legacy matters. It really does. The phrase ‘Think Global, Act Local’ was first used in the context of environmental challenges, but has now been used in various settings, including planning, education, mathematics, and business. If you wanted to achieve change and improvement, you can’t wait for global legislation or global action. The best course of action is to drive change yourself. YOU could act to reduce YOUR OWN environmental impact by, for example, consuming less energy or water, or only buying clothes that you need (preferably second hand.) Acting locally starts to address what you see as a global issue. Every time someone forgets to turn the lights off in the office or at home, I remind them of the polar bear’s hardship to hunt for food. Any human, and any animal, needs food! You can’t argue what you saw in the video, because our unsustainable rate of energy consumption and development really is affecting them. Normal people (with feelings) can’t help but feel so sad for them. It’s an easy connection to make. Polar bear survival = turn the lights off. Don’t forget, actions also speak louder than words. Doing what YOU do is a step closer to having OTHERS do as YOU do. Here is a quick rundown of the really, really, simple things YOU can do now, in each of the problem areas we’ve touched on above:

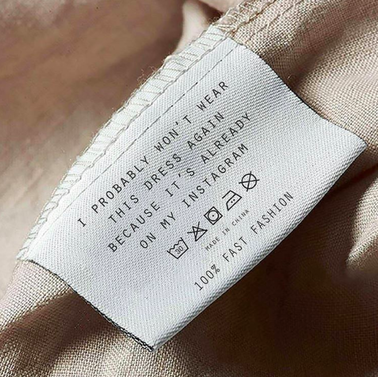

Ditch Your Fast Fashion HabitsAs for fashion, let’s not even use that word. Let’s just call it for what it is: the shirt off your back to protect you from the elements. Think about how many items of clothing is basically necessary for your wardrobe, which goes hand in hand with function. As we commemorate the events that transpired prior, during and after the Rana Plaza disaster, may I remind you – making clothes doesn't need to have a human cost. We should all work in satisfactory conditions, get paid for a day's worth, and come home safe. The death toll was 1,138, with many more injured. That's way too many. And that doesn't include other factory fires in Bangladesh and others around the globe. So let me tell you: if you think not buying a $10.00 top is not making an impact on the fast fashion industry, you are truly wrong. Your individual action and others who do the same are telling the world the horrid conditions these workers have to endure to make a living is unacceptable. You are avoiding THIS from happening again: I have been researching the apparel-making industry, the rise of Fast Fashion and its supply chain and ethical issues for a while now. Yes, we need clothes. But we don’t need fashion. We can look stylish however, and wear items that match our personal style, as well as feeling great in them, right? You can achieve this. If you’re worried about price, shop second-hand or organize a clothes-swap with your friends. When I did not shop for new clothes in 2007, and then 2017, I managed fine. If I needed a wardrobe refresh, I’d go to my favourite op-shop, the North Perth Red Cross store on Fitzgerald Street. Look for pieces that match your existing wardrobe, that can be worn/layered for all seasons. For starters, as a rule, you can buy new underwear and new running or work out shoes if you’re an active person. You can accept gifts but try not to gift somebody else new clothes. There are other rules for years 2, 3, and so forth, which I’ll get to later on. One thing that really had an impact on me was to stop subscribing to this online retail marketplace, called BrandsExclusive.com.au. I did that in 2016. Not seeing their weekly or daily specials in my inbox really helped me stay away from unnecessary spending. I highly recommend unsubscribing to most, if not all of online shopping temptations. The solution is not to boycott clothes from certain brands, because the fashion supply chain is a complex relationship and transparency cobweb. Instead, give some thought about the price of the product, because cheap clothes = dead people (see image above.) Say no to Fast Fashion now. When all is said and done, the solutions are within your reach, after all. Take action today. You CAN be a power of change. Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity Tags: #conscientiousfashionista #fastfashion #slowfashion #ethicalfashion #ecofashion #sustainablefashion #greenfashion #sustainability #wardrobetruths #fashioneducation #fashionisnolongertrendy #fashion #ranaplaza #bangladesh #FashionRevolution #thinkglobalactlocal Further reading:

1 Comment

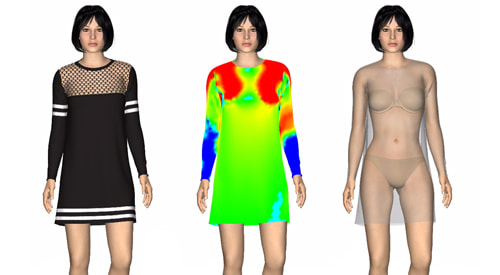

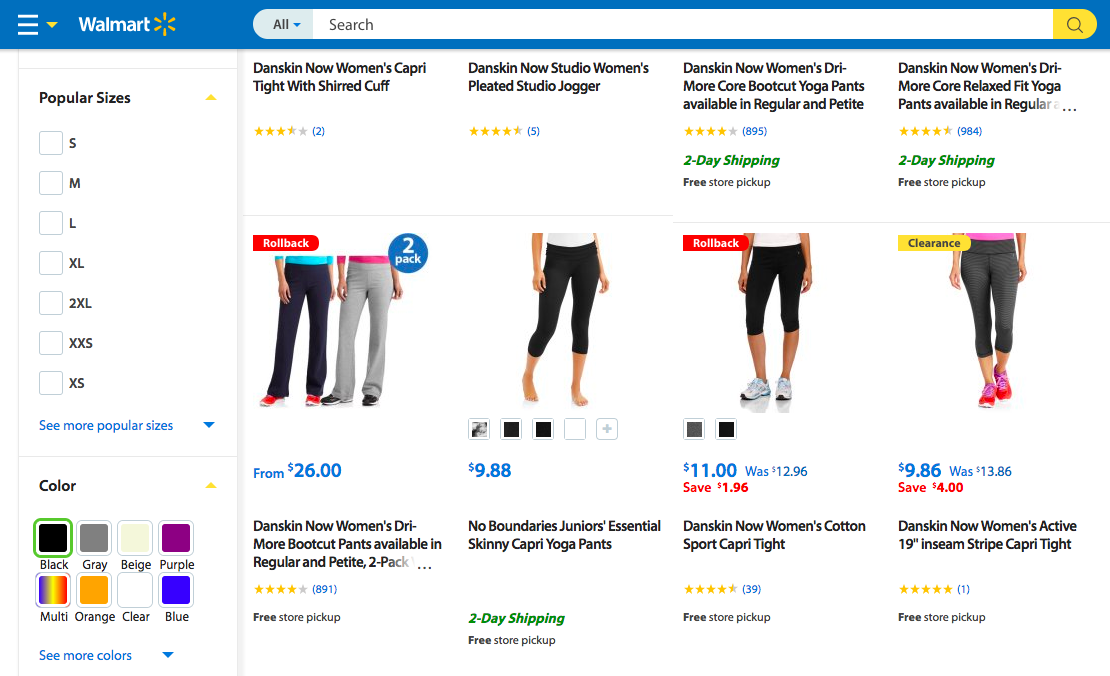

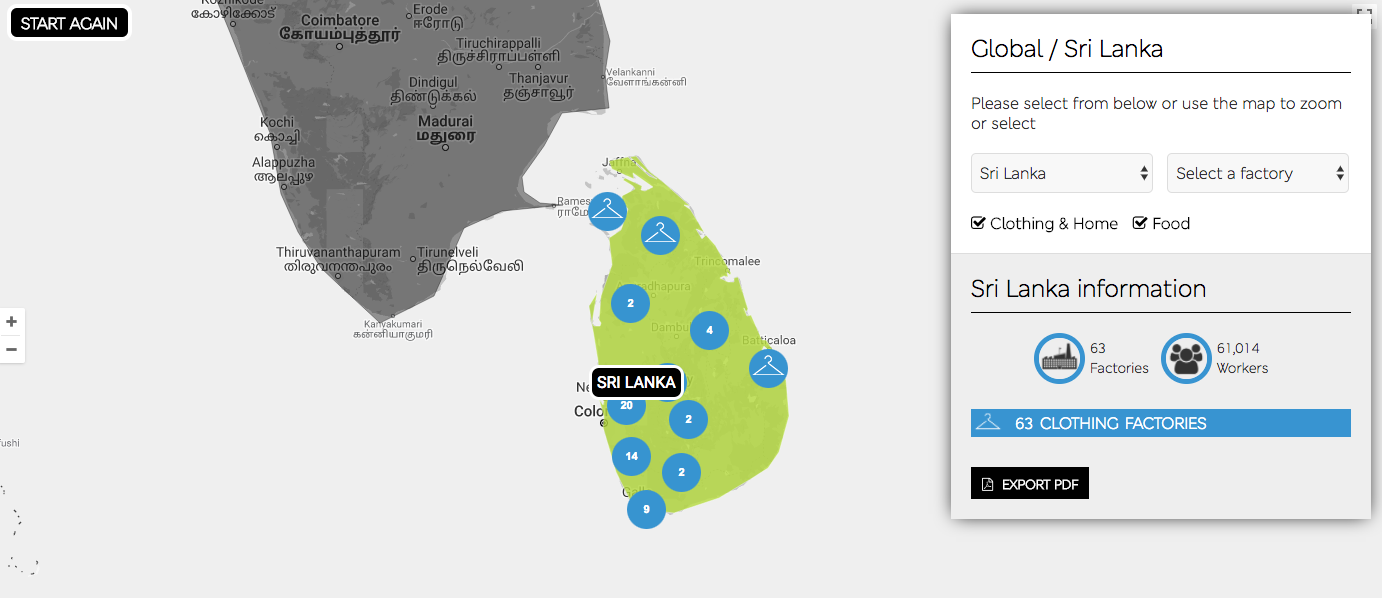

Special Report on the International Conference on the Apparel Industry 2556 words; 13 min read Sri Lanka and Fashion Earlier this month (February 7-9th) I had the privilege of attending the inaugural International Conference on the Apparel Industry, held in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The event was organised by Monash Business School, Monash University, Australia; Joint Apparel Association Forum (JAAF), Sri Lanka; University of Warwick, UK; University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka; Postgraduate Institute of Management (PIM), Sri Lanka, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka; University of Dhaka, Bangladesh; Institute for Manufacturing, Centre for Industrial Sustainability, University of Cambridge, UK; and the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, Sri Lanka. Globally, 60 million people are employed in the apparel or garment industry, with around 15 million employed (largely women) in factories located in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Asian manufacturers supply a very large proportion of the garments sold in developed countries. This year's conference focused on Productivity Improvement, Disruptive Innovation and Leadership. For me, an environmental problem-solving professional who did not have any formal training in fashion, merchandising, apparel making, textiles and fabric creation, pattern making and dyeing, and so forth, I was hoping to meet people in the industry who are. And boy, oh, boy, did I meet them! There's nothing like asking the people who you want to work with how they feel about the idea you are trying to sell. In my case, compulsory environmental footprint labelling on clothes. (More on this later.) And so, on this occasion, the Conference was my first foray into this strange world I'm about to dive into, and how I fit into some parts, if any, of it. Well into the first hour, it's apparent I'm not completely out of place. Even though I am no expert in fashion design, buying textile, or drawing sketches, trying to imagine the way a fabric flows… I am no stranger to manufacturing, where half of my career has been focused on. I am a sucker for process, and I never think about problem-solving without understanding where I belong in the scheme of things. I understand the mechanics of production. And that's something a lot of us in the room had in common. The elephant in the room The Conference's theme did focus on taking your apparel business higher up the value chain. For those who are uninitiated, value chain refers to all the activities, from receipt of raw materials to post-sales support, that together create and increase the value of a product. Reason being: to be competitively advantageous. The phrase "moving up the value chain" essentially means using business processes and resources to produce highly profitable products, also known as higher-margin products. Mr. Riaz Hamidullah, High Commissioner of the People's Republic of Bangladesh to the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, in his keynote speech on Day One, had to remind the Conference attendees that the Apparel Industry has some big structural and governance problems before it can move up the value chain, though. The elephant in the room has everything to do with sustainable consumption, and not just the way we produce clothes in Asia. We weren't able to formally discuss the problem of the current unsustainable consumer habits during the course of the Conference. Nevertheless, he made a great point, and further along in my analysis I'll try to take the elephant out of the room for everyone to notice. For those who've read my posts, you will no doubt already appreciate the fact that I believe the fashion industry is responsible for cleaning this mess up. The elephant in the room has everything to do with sustainable consumption, and not just the way we produce clothes in Asia. Export quality versus 'other' Perhaps ‘moving up the value chain’ resonates more with the export garments market, and very much relevant to Sri Lanka. If this is confusing to you, let me explain. Export market garments generally are made from higher quality materials, fabrics, and prints for the sophisticated consumer. These consumers expect aesthetically pleasing, on-trend clothes that are equally durable and perform well. The export garment industry is Sri Lanka’s primary foreign exchange earner accounting to forty percent of total exports and fifty-two percent of industrial products exports. Sri Lanka prides itself as the ‘ethical’ choice manufacturer of apparel for the export market, and has gone as far as being totally self-regulated, with the mantra ‘Garments Without Guilt’ and corresponding certification being used by the industry to demonstrate responsible business practices and assure international buyers of working conditions in the country. This means, the garments they produce are sold as ‘high-end’ apparel. There’s a reason certain clothing brands claim their products are high-end. Apart from the two biggest costs to producing clothes – the manufacturer and the fabric – there’s the cost of compliance. Substance regulations, labelling requirements, documentation requirements, and lab testing requirements all vary by import country. One of the more important factors to consider is the not-so-cheap costs of making compliance requirements happen. Clothing textiles are regulated in most countries, including the United States, Europe and Australia. Most applicable safety standards, such as REACH (Europe) and FHSA (United States) regulate substances, such as formaldehyde, AZO-colours and asbestos. Now let’s look at the industry in general. Most Chinese manufacturers, especially the smaller ones, are not aware of the substance content in their textiles. (China is the biggest clothing manufacturer in the world, by the way.) According to this source, it’s a deeply rooted issue that goes way beyond the manufacturer. All clothing manufacturers purchase fabrics and components from subcontractors. The number of subcontractors can range from a two or three, to more than one hundred. Apart from the two biggest costs to producing clothes – the manufacturer and the fabric – there’s the cost of compliance. The best reflection of compliance to standards is the price of the product. Take, for example, lululemon Athletica, the Canadian athletics apparel retailer. A pair of their best-selling three-quarter yoga tights retail for US $128.00. I know for a fact that they are manufactured at MAS Holding’s Shadowline factory in Katunayake, a highly efficient and lean factory that I had the privilege to visit on the last day of the Conference. The price of the lululemon tights, compared to a US $10.00 similar pair from Walmart, paints a story of two worlds. Yes, those yoga tights may be compliant to USA regulations for imports to be sold at Walmart stores. But it still raises questions, doesn’t it? Additionally, does it make sense now that clothes made for the Asian market, for example, are of inferior quality? Lower-income households in Asia have always only bought clothes that they needed, due to their restricted budget. Whether or not these garments are of high quality, is not the issue. Fast fashion caters for those who have disposable income and encourages unnecessary spending on stuff you don’t actually need. The apparel manufacturing market for the locals may not cater for discerning first world tastes, but that is because they value function and their wages, more so than aesthetics. Perhaps, even, making sure they have enough food to eat and that their children go to school is more of a priority than buying on-trend clothes. Are manufacturers ready for digitisation? Professor Amrik Sohal, in his opening presentation, mused about how they started on this journey. About four years ago when Monash Business School was looking at the challenges of this industry, they made a concerted effort to analyse Bangladesh’s Ready Made Garments (RMG) industry as a case study. Discussions were held with factory owners, garment merchandisers, as well as governmental departments and management professionals in positions of influence. After much analysis, they presented their findings to the country’s top officials and a national forum was held. In summary, Bangladesh sat on the lower spectrum of the industry in terms of supply chain value. As a whole, the industry is still reliant on local and overseas business for quantity of products delivered, as opposed to quality, due to its relatively cheap labour costs. When I was in Katunayake, I didn’t feel like I was in an unindustrialised nation. So when we start discussing value chain and product edge, Sri Lanka has embraced this, as evidenced by the factory visits I attended as part of the Conference. The three facilities I visited are all situated in Katunayake, an industrial estate a stone throw's away from the capital city's airport: MAS Holdings’ Shadowline factory, which specialises in making fitness and activewear garments, Hirdaramani’s factory that specialises in knitted garments and children’s clothing, and STAR Garments' Innovation Center that focuses on STAR’s digital expertise to produce prints, samples, and pattern making, among others. The Innovation Centre was officially opened in October 2017 and is the first passive house designed in South East Asia. (In Europe, passive houses are designed to keep warmth in, but in this case, keeping conditions cool.) When I was in Katunayake, I didn’t feel like I was in an unindustrialised nation. These factories are heavily audited to international manufacturing and quality standards, are fully compliant with their regulatory licences, and most importantly, values their people. Keeping in mind that Sri Lanka Apparel is a signatory to 41 of the total number of conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO), and the only country with a significant manufacturing industry to do so, they have to look beyond cheap labour to provide value, and are well on their way in implementing productivity improvements and innovation. It was clear to me that MAS Holdings, for example, has fully applied vertical integration in their supply chain to deliver short lead times to provide value to their buyers. One of the challenges of the apparel industry is undoubtedly the laborious aspects of assembling clothes. (I shall reserve my commentary on the textile production side of the industry for now, as the conference did not touch on this.) It seems to me that in most parts of the industry in this region, the churning of the quantities in lighting speed time and at the cheapest possible cost – is still the preferred way to do business. After the panel discussions and the factory visits, it’s obvious that the industry as a whole in Asia, even though within close geographical proximities to one another, has a long journey ahead in embracing value-added, high-end manufacturing of products. ....the churning of the quantities in lighting speed time and at the cheapest possible cost – is still the preferred way to do business. The other apparel-making countries; notably China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, India, Hong Kong, Turkey, and Indonesia – how can they prepare themselves for Industry 4.0, when the basics of safety, transparency, and compliance is still problematic? Fast Fashion still responsible Well, they may not be ready. But that’s not entirely their fault. The disruptors in the apparel industry have perfected the fast fashion retail model, where trends are created based on what’s going on the street, ditching the two-season cycle of sales altogether. These brands know what it takes to successfully set up fashion retail operations with omnichannels, they have considered imports and exports across regions, and they have a scientific inkling on measuring supply and demand. Manufacturers of garments in Asia didn’t really get a chance to have a say in the way fast fashion works: they just had to bear the grunt of the demands placed on them. It kind of happened really quickly, and the Asian factories were only eager to be part of it. The big brand players placed heavy emphasis on the manufacturers that fashion retailing had changed; that this is the new world order; and if you did not meet demand, then you’re not going to reap the benefits. It’s a revolution of a treacherous kind, though. If the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh didn’t teach us anything, then what can? The societal and environmental impacts in delivering these ‘fashionable’ pieces are much too great. Compliance to safety standards is one thing, but as Professor Jan Godsell, from Warwick Manufacturing Group, UK, said in her keynote address at the Conference, “...the current model of economic development is broken. We can’t have economists measure the success of businesses by how much they sell products that consumers don’t actually need.” This is the elephant in the room problem Mr. Hamidullah mentioned on Day One. It’s been almost five years since that fateful day in April, and the international brands that manufacture in Bangladesh are still nowhere near cleaning up their act in terms of improving fire and building protocols and being accountable for their supply chain. A December 2015 report, written by the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, found that only eight of 3,425 factories inspected had "remedied violations enough to pass a final inspection" despite the international community's $280 million commitment to clean up Bangladesh's RMG industry. Sarah Labowitz, the co-author of the 2015 NYU study, sees the flaws in the efforts to remediate Bangladesh’s factories. “[The unfinished remediation] also demonstrates the limits of the model where you basically push all the responsibility and the blame onto factories. There needs to be more accountability for the brands themselves… In some ways, the Accord and the Alliance, they’re the most intense version of a strategy that's been tried for 25 years to try and reform bad factories. And it’s just not working.” The power play As we stand today, the apparel industry in Asia may well be just that one step behind in trend setting, but they know how production works. One of the more prominent debates coming out of the Conference was the fact that the regional manufacturers’ supply chain linkages are strong. This is the kind of knowledge that the buyers and fashion houses, headquartered in Europe, USA, or Australia are far removed from. Monash University has been looking into this as part of their research into sustainability in apparel manufacturing, and thinks this makes for a compelling case of reversing the demand power balance. "....We can’t have economists measure the success of businesses by how much they sell products that consumers don’t actually need." This journey counts After some heartening and equally disheartening conversations in Sri Lanka over the course of three days, I remain optimistic. I was in bed with good company. If anything, Sri Lanka has shown the conference delegates how the foundations of sustainability can be erected. I can only hope that the appetite for making quality garments continue within the region, and that consumers and manufacturers keep demanding safer, and fairer practices for themselves – this is the real ‘trend’ that is going to shape the apparel industry. In parallel, advocates and governments can push the agenda of regulation, too. This disruption and innovation journey is so important. Sri Lanka is only the beginning. Our conversations today will pave the way for the right leadership to move ahead with confidence and competence. To close, I quote Professor Godsell, “We can be a part of the changing trends, not a victim of it.” The future looks bright from here. Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity. Tags: #conscientiousfashionista #fastfashion #slowfashion #ethicalfashion #wardrobetruths #fashioneducation #fashionisnolongertrendy #digitisation #SriLanka #apparel #textile #clothing #passivehouse #srilankanapparel Useful links:

Please note I was not paid to go to the Conference, and all expenses of the trip was beared wholly by me.

We tend to lament the fact that our mobile phones are seemingly built in a way that their peak performance will expire after about two years. Officially, there’s a term for this: Planned Obsolescence. Anyone notice how our clothes’ vibrancy and quality don’t last, either? 1340 words; 6 mins read Updated 5 Nov 2018 Last week, French consumer protection authorities initiated an investigation in response to reports that Apple deliberately shortened the life span or effectiveness of its products in order to prompt increased consumer demand to replace them. In December 2017 Apple acknowledged it intentionally slowed down iPhones with older batteries, but said the move was made to extend the life of its products. In reality however, planned obsolescence is not a new concept. Planned obsolescence occurs when a product designer creates a design that is meant to phase out after a certain period of time. This makes the product have a lifespan of a limited duration, often influencing consumers to upgrade to a more expensive or newer model. For example, light bulbs may burn out right after their warranty period, non-removable batteries may be used on certain electronics, spare parts may not be available for certain vehicles, and fashion trends may make clothing quickly come out of style. What’s bad about Planned Obsolescence is that it makes it obvious to the consumer that products that we buy cannot be considered a ‘forever’ investment, but as a ‘good for a few years’ kind of purchase. As a result, we have to fork out more of our hard-earned money to buy more new things, even if the product or a part of the product is working completely fine. Think about the amount of energy, resources and money that all of this needs. Not to mention the amount of waste that we as a society generate from this model. The reason? For companies to make moolah, simple as that. On the plus side, our disposable habits sustain jobs for people who design and produce stuff. But does this mean this is the right thing to do? The right thing to do is to keep honing and at the same time nurture the right skills. Skills from people who repair stuff. Yup, we need to mend things more – clothes, shoes, buckles, buttons. Fix things by servicing, give parts some lubricant, change over mechanism, replace the inner workings of a computer or fridge or clock. Yes, at some point things do break down. But they should really be designed to last forever. In the case of buying software, for example, the argument to support buying a new version of Microsoft Office for light personal use, is less than compelling to me. It’s funny that some things we want to last forever – like diamonds, and Rolex watches and grandma's vintage wedding gown. But some things we don’t give a stuff about. Why is this? Why can’t we appreciate things that we have now, tomorrow? Or twenty years from now? Or fifty? We’ve been conditioned to think this is the way things are, so we accept it, but I can tell you – it wasn’t always like this. It all started with the American automotive industry back in the 1920’s. Read up on this topic on Wikipedia. What’s tragic about this whole concept is that there are two dimensions to it: The functional obsolescence of a product, and the perceived obsolescence of a product. In the world of electronics and some moving parts, there may be an argument that obsolescence is necessary, but it’s really limited to innovation (and even so, one may argue this isn’t genuine innovation) and so-called product improvement. In the world of fashion, it’s obvious the reason we buy new clothes more regularly than our previous generations was because of the heavy influence of ‘trends’ and the affordability of ‘not made to last’ garments – hence, ‘perceived’ obsolescence. I admit, I still have many friends who shop for function and purpose. But a growing number of young people are buying clothes to get a kick out of having something new, not necessarily because they actually need it. Planned Obsolescence that play with our minds; the psychological form of it. We wear clothes to protect our body from the elements, to play sports, to go to work. There are functional elements to these. But buying clothes when your wardrobe is still full of items you hardly wear? There’s no real necessity. This 2012 published paper by several authors from universities in USA, Canada and Hong Kong has looked into the rise of Fast Fashion and how this new wave of consumerism makes a case for Luxury Brands to champion the sustainability movement in the industry. (I shall touch on sustainability leaders in the fashion industry in later weeks.) In it, a number of participants, aged between 21 and 35 were surveyed about their purchasing habits in relation to their personal values. It summarises that even though some participants have an increased awareness of environmental issues and aligned their actions to positively impact the cause, they don’t relate consuming cheap chic as a contributor of environmental monstrosity. The study also confirms the unnecessary consumption of fashion due to purely aesthetics reasons. As one student participant eloquently puts it, “…when I see it on the catwalks or in magazines, I want it immediately.” On perceived obsolescence, the study quotes Abrahamson (2011), in that he observes "Fashion, more than any other industry in the world, embraces obsolescence as a primary goal; fast fashion simply raises the stakes.” "Fashion, more than any other industry in the world, embraces obsolescence as a primary goal; fast fashion simply raises the stakes.” Is there a case for making products that last, though? Of course! Encouragingly, there are brands out there that have garnered true fans from around the world by being ‘forever’ brands that consumers can rely on, even with normal wear and tear of their products. Case in point: Osprey, the bag/backpack manufacturer, whose “All Mighty Guarantee” promises their customers that “..they will repair any damage or defect for any reason free of charge – whether it was purchased in 1974 or yesterday. If we are unable to perform a functional repair on your pack, we will happily replace it.” Here is a link compiled in 2016 of brands that have lifetime or limited guarantees on their products. Have you heard of Fairphone? It’s second-generation mobile phone, which was released in 2015, made a virtue of having components that could be easily swapped out by the device's owners, even if they had no technical skills to speak of. By making a device with simple-to-replace parts, Fairphone is well on its way to reverse the Planned Obsolescence strategy; by extending the lifetime of its smartphones by fixing what’s broken only. In a way, this notion of thinking about the lifecycle of a product can be attributed to extended producer responsibility (EPR), or product stewardship. In the meantime, we have to change our own ways of thinking. Green Alliance, a charity and independent think tank in the UK, encourages a #circular economy where people repair, sell, and re-use devices – check out their 2015 report on opportunities in the UK, USA and India for the technology industry here. Perhaps the fashion industry needs a similar alliance! Hopefully you as a consumer are wise enough to understand that even though we are part of this wheel of mass consumption, we can break away from it, little by little with the value of every dollar spent. Spend it on the things you absolutely need, and on brands that will value you. From now on, every time you’re faced with an impulse to buy a dress off the racks just for occasional use, just think out loud: will you be tricked again? Dollars speak volumes. The signal you’re sending to Fast Fashion will be much louder, and clearer. Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity. Tags: #conscientiousfashionista #fastfashion #slowfashion #ethicalfashion #wardrobetruths #fashioneducation #obsolescence #plannedobsolescence #fashionisnolongertrendy #tricksofthetrade #fashion #gadgets #technology #circularity #circulareconomy #plannedobsolescence References:

Abrahamson, Eric (2011) “The Iron Cage: Ugly, Cool and Unfashionable.” Organization Studies 32: pp615–29. Why It's Normal That Stella McCartney's Latest Campaign Was Shot In A Landfill (web), last accessed 16 Jan 2018. Increased fetishising of cheap clothes has led us to prioritise quantity over quality. With this degradation in the fashion landscape, has fashion itself lost its meaning? Grandma might have a thing or two to say about it. 1529 words; 7 min read Updated 5 Nov 2018 The phrase “fast fashion” refers to low-cost clothing collections that mimic current luxury fashion trends. Fast fashion helps sate deeply held desires among young (and not-so-young) consumers for luxury fashion, a world that embodies pieces of clothing, high-end jewellery, and jetsetting lifetyles that is unattainable to many. The changing fashion landscape, however, has undoubtedly led to the degradation of society as consumers. And we’re not wholly to blame for it. Read on to understand why. There used to be structure in fashionBelieve it or not, once upon a time, there was structure. The production model was based on a critical distinction between 'fashion' and 'garment'. At the top of the tree was couture. Its unique selling proposition (USP) was the amount of skilled labour inherent in every piece. The look was in the hands of the #designer and creator, and the volume of repeated pieces was limited to tens at the most. Final finishings were typically #handmade, and the buyer might not see the finished product until the very end of the process. Guess where the fashion weeks come from? You guessed it, and this cycle occurs twice a year only. (Check out this great low-down on Haute Couture by British Vogue.) And then there was Ready to Wear, or Prêt-à-Porter. Ready-to-wear has rather different connotations in the spheres of fashion and classic clothing. In the fashion industry, designers produce ready-to-wear clothing, intended to be worn without significant alteration because clothing made to standard sizes fits most people. They use standard patterns, factory equipment, and faster construction techniques to keep costs low, compared to a custom-sewn version of the same item. Some fashion houses and fashion designers produce mass-produced and industrially manufactured ready-to-wear lines but others offer garments that are not unique but are produced in limited numbers (industrialised limited cuts.) And then there are the basics. Like your jeans, your t-shirts, and undergarments. This is the structure. Fast-forward to now, Fast Fashion has unsustainably fed our wardrobes by linking everything we buy to have a direct lineage to the runway somehow. We've entered a new era of consumption (or, as you may recognise as 'fashion') where we can now 'design' styles inspired by the runway and hang garments in a shop rail in as quick as three weeks. Even wardrobe basics are expected to be infused with the aura of big design and big designers. So-called style trends followed, once we kept up with more carbon copy production and consumers started purchasing and wearing the same pieces. “We live not according to reason, but according to fashion.” – Seneca The degradation of the fashion landscapeIt’s genius, though. For consumers, not for the environment. As stated above, most people see high end luxury as something unattainable. This world conjures up images of exclusivity, beauty and art, and dream-like settings. In a way, Fast Fashion fills that void in that our fantasies can now come true. Our thirst to fulfil this dream is so big though, that it cannot be fed completely, and it’s ever-lasting. The couture houses are now seemingly perpetuating the problem, too. Instead of only producing two seasons’ worth of collections, we now have other ones gracing the runways – ‘capsule collection’, ‘resort collection’, 'pre-fall', and similar. The Zara production model for example (I'll discuss this later on) focuses on the creation of smaller-than-average production batches to overcome the dizzying rates at which trends evolve, which in turn provides for limited floor stocks for its designers' creations. As a result, the average consumer, seeing the last pair of size 8 blazer on the shelves that fit her, is then tricked into thinking affordable 'fashion' will be gone forever if you don't snatch it now. Harvard researchers (2004) have described this drives a sort of hunger... 'a sense of tantalising exclusivity.' What this means for usThere's a sweet irony to all of this. The industry's foray into 'dynamic' fashion has created a consumerism monster – and as a consequence, they are constantly chasing their own tail. This pandemonium is what ultimately keeps the weaves turning. It is then fair to observe that the industry's meteoric rise due to Fast Fashion has peaked, and it's on a spiralling comedown. Fast Fashion has become a bit ugly, and tacking it is like getting into an argument with someone who's physically bigger than you, that is difficult to neutralise. In the meantime, in people's homes all around the industrialised nations, this is the resultant reality we're faced with. Picture this: your burgeoning wardrobe with clothes hanging out of them with tags still on. The rush of people busting at the doors at Boxing Day sales. The way we simply just throw away our clothes because they were a 'bargain' discounted buy, purchased for a mere $5. The problem with attainable cheap ‘fashion’, is that you have too much choice. Ask yourself this: despite your hard to shut drawers and fat wardrobe, philosophically speaking, it is highly likely you won't be happy with what you got. Essentially, how many mornings you do wake up to go to work, a party, a wedding, a dinner date… Thinking you can’t find ANYTHING to wear? "Maybe all your clothes should past the Grandma test." All is not lost, however I remember my conversations with my grandmother when she talks about how she bought her washing machine two decades ago and it’s still going, after about three repaired breakdowns. She comes from a generation that repairs and mends things, not throw them away because they’re a little troubled. I always thought grandma’s philosophy of quality over quantity was potent advice that made sense. Her words of wisdom have stayed with me and have gotten me through lots of hype over my growing up years. Maybe all your clothes should past the Grandma test. Grandma’s right though, isn’t she? Quality always wins over quantity. Except for children’s clothes, I get that (in some cases though, not all.) In grandma’s world, the hand-me-down philosophy makes perfect sense for children in a family. I never wore new clothes when I was younger. I always wore dad’s daggy work pants that he stopped wearing, the ones with the pleats. And did I end up an adult with negative scars from my ‘styling’ sense? I don’t think so. I am nowhere close to say I can conjure up Grandma's memories and things that bring her nostalgia. She'd been through the war so I have no authority whatsoever on the topic. But I don't think it's quite a stretch to say I am sick of mass consumerism. Can we bring art, beauty, dreams, and exclusivity back please? I’d really like to see the end of Fast Fashion, pronto. How many times have you walked in a clothing shop for a browse, and thought to yourself: Wow, these cheap, polyester blend clothes on the racks are so….. unattractive! And uninspiring! And quickly thought that window shopping idea was a bad one? Grandma doesn't go out anymore because of her bad legs, but I'd be ashamed to take her clothes shopping at the mall. It's beyond embarrassing. She taught me lots, and I can attribute my sense of style to her. She instilled in me that we can have our own luxuries in life – from the few 'good' things we own – that we will treasure forever. That's why we appreciate the clothes from their era so much. The fabric, the stitching, the way the seams were put together. You can actually feel the luxury. When grandma reminisces on the good ol’ days and you see that spark in her eyes... you know she means better quality products, better quality clothes, better quality furniture. Yes, contrast this to the story about the burgeoning wardrobe above. Which brings me to this: are we only pretending to feel good in our cheap clothes? Well, maybe you can change that today. Try buying quality-made products that lasts you more than thirty wears. Can we look at buying clothes a bit differently from now on? Be a little rebellious. Invest in something you really love when you're next at the shops, something that would make your grandma proud. Stay tuned for the next write-up! Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity. Tags: #createyourtrend #styleoverfashion #liberation #freeyourself #fastfashion #slowfashion #ethicalfashion #responsiblefashion #intentionalpurchasing #fashioneducation #wardrobetruths #whomademyclothes #fashionisnolongertrendy #grandmaknowsbest References: "Rapid-Fire Fulfillment," Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82, No.11, November 2004.

As a society, we should be ashamed of ourselves. We haven't really tried very hard to reduce our impact of consuming fashion, because we don't even know how they're made. 1585 words; 7 min read Updated 5 Nov 2018 We see so many companies claiming to manufacture ethically, or producing sustainable fashion. But let's get back to basics. We can't be buying into fashion trends or ethical fashion claims, when we don't even understand how clothes are made. If we were all students in a classroom taking a test on what and who made our clothes, we would all fail – tremendously. In the process of explaining my venture to many, many people – the Uber driver taking me to my destination, my high school friends, my ex-workmates, even my siblings, it's clear that we are dumb about where our clothes come from. There are so many levels of inputs into the supply chain of garment production, that we don't seem to care or appreciate. We see something we like on a shelf or hanger, and if it fits well (arguably, sometimes it doesn't fit well but it's cheap enough), we snatch and pay – simple! Inherently, all clothes carry an environmental footprint. Natural fibres are not always the better choice. Consuming fashion should be easyHow do I choose better, then? Well, when it comes to choosing a piece of clothing from the shelves, consumers are driven by their own values. These are so deeply rooted and so varied in each individual, we can never gauge in which direction this decision could have its origins. We have to wear clothes, sure. This is not a fabric-shaming exercise. One fabric is not better than the other. But wouldn’t it be great if you knew some of this info at point of purchase? What I am championing for, in this day and age, is that clothes are labelled for its environmental and social footprint. This is so that consumers can make a value-based decision that matches their own. We already do this – the food we eat based on the labels affixed on the can, or how it's described in an upmarket restaurant's menu. The furniture we buy because we know of its make and origins, and fall in love with its texture, grain, feel to touch. The drinks we avoid because we know of its sugar content. The cars we drive because we know of its emissions and where it's assembled, and so forth. For example, we are proud to announce our wines come from a certain region, that our cars are German, that our eggs are free-range, and that our dining table is jarrah or oak. But boasting about how much water my jeans consumed in the production process? Not that sexy, is it? But at least with a footprint label, you know. You can’t ‘un-know’ what you’ve been told. This may be a purely educational exercise, or it could actually influence purchasing decisions. What do you reckon? (I expand this idea further throughout the blog.) The natural versus synthetic conundrum The most common question I get when I dive into this topic is the fabric used. Ah, the old which fabric is greener conversation. Are natural fibres (cotton, wool, silk) better than synthetics (acrylic, nylon, polyester)? Inherently, all clothes carry an environmental footprint. Natural fibres are not always the most ethical or sustainable choice. (While we’re on this topic, leather is not technically a fabric but a material.) In terms of natural fibres, cotton is the thirstiest yarn on the planet, whereas bamboo and hemp are must faster-growing and is less resource-intensive. Cotton also relies heavily on pesticides and insecticides to ensure maximum yield for growers. Synthetics mostly originate from the distillation of petroleum and carries with it the footprint of mining for oil, refining, and distribution which constitutes a big chunk of environmental impacts to air, land, and water. There's also rayon (viscose), modal, and lyocell, which the industry terms "regenerative" cellulose fibres. Unlike most man-made fibres, rayon, modal, and lyocell are not synthetic. They are made from cellulose, commonly derived from wood pulp, and more recently from bamboo. They are neither a truly synthetic fibre, in the sense of synthetics coming from petroleum, nor are they natural fibres, in the sense of processing fibres that are produced directly from plants or animals (such as wool.) However, their properties and characteristics are more similar to those of natural cellulosic fibres, such as cotton, flax (linen), hemp and jute, than those of thermoplastic, petroleum-based synthetic fibres such as nylon or polyester. More on this here. Not all clothes are 100% of a certain fibre. We find cotton mixed with elastane, cotton silk blends, acrylic blended with wool, and polyester regularly mixed with other fibres. So your clothing footprint is all jumbled up! What I am championing for, in this day and age, is that clothes are labelled for its environmental and social footprint. Fabric is only one part of making clothes happen What people often don’t think about is that the fabric selection is only one part of the garment manufacturing process. In a nutshell we have the following steps:

But hang on – even before we get to garment manufacturing, how did your fabric get there? Consider step (2) above, “sourcing your materials.” Your yarn did not come to a wholesaler’s office in rolls straight from an Uzbekistan cotton farm, or from a petroleum distillation refinery. A big dirty part of it howeve Yes, turning fibre into fashion is a dirty industry. This is where we focus our minds next: to the textile industry and its mills across the globe. The #textile industry is primarily concerned with the design and production of yarn, cloth, clothing, and their distribution. The raw material may be natural or synthetic using products of the chemical industry. We tend to assume that fashion has moved into some high-tech zone, with garments produced by magic pollution-free processes, but it is far from it. Take natural fibres, for example. Turning white fluffy cotton bolls into fabric, washing the grease out of wool – often remains the back-breaking, pollution-riddled heavy industry it ever was. We might be fooled to think the process has now become ‘clean’, but the reality is, we just don’t see them – because it no longer happens in our backyard. Textile #mills are found in China, India, Italy, Germany, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. In over a hundred years, the essential process (and some of the chemicals) used in textile production really haven’t changed much. As anti-pollution laws came into effect to protect First World inhabitants and resources (for example, the USA Federal Water Pollution Control Act 1972), the fashion industry, with its penchant for quick and cheap, switched its production game to parts of the world that are harder to monitor, and where they also often benefit from less stringent, or non-existent, legal controls. Now I’m not saying all of textile production is bad, I’m saying most of them in Developing World countries probably wouldn’t meet your expectations if you were to visit one. After all, 90 percent of waste water in developing countries is discharged into streams and rivers without any treatment. The truth is that, without a plethora of toxic substances or processes to choose from, your wardrobe wouldn’t be half as visually appealing or work so well on your bodies. With the exception of some pretty dire eco-fabrics (think jute and hemp – not everyone's cup of tea), a fabric can’t go anywhere until it’s finished, least of all into your washing machine or even the open air, where it would disintegrate and drip dye all over your house. We just need to start with existing measures first – the basics With all that in mind, what has come of us – society at large, is that we’re first and foremost consumer of garments, and secondly (if applicable), religious trend follower of Fast Fashion. You probably know by now that Fast Fashion is not good for our planet. The resources it requires is putting extra pressure on our environment and people, in a negative way, while big corporations are only interested in making more profit for themselves by squeezing tight the cost of production – mainly in the form of wages and raw materials, and avoidance of compliance. I don’t think we’re anywhere near solving all of Fast Fashion’s problems, or even any close at reversing the trend. But governments can regulate our factories better, right? And monitor compliance to standards? To treat wastewater prior to discharge? To install filters on our stacks? To make sure people who work in textile mills wear appropriate personal protective equipment? Are these new concepts to you? I doubt it. Once we do this, the cost of producing textiles will take into account the health of our rivers and the air we breathe, the health of our workers, the wellbeing of our societies and ecosystems. Then we can really go back to basics. Make clothes because we need and appreciate them; not because they are #trendy, according to Fast Fashion. Perhaps it’s not really an insurmountable idea to live in a world where we intentionally purchase our necessities based on what works for our bodies. I’d like to imagine so. Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity. Tags: #wardrobetruths #lessonsinfashion #ethicalfashion #fastfashion #slowfashion #fashionisnolongertrendy #fashioneducation References: Siegle, L. (2010) "To Die For - Is Fashion Wearing Out the World?

Our middle class is no longer. With the tightening of our household budget, everyone wants cheap. We don't sacrifice looking good, so enter Fast Fashion. 461 words; 2 min read Updated 15 September 2018. In 2002, (now Sir) Philip Green bought the Arcadia Group for £850 million. In 2005, his star brand Topshop accounted for £1 billion of UK clothing sales alone for the first half! (A feat, considering the entire clothing market was worth £7 billion.) Fast forward to 2017, Topshop Australia is now under administration, and Topshop globally is under nobody's radar.. recording losses in revenue year on year. His other brands including Dorothy Perkins, Evans, and Wallis, among others are also no longer relevant. It seems that buying clothing nowadays is limited to just cheap clothes, and expensive clothes. There is no middle-ground fashion. Take Myer Australia, for example. Once the icon of Australian retailing, it is on the slide with the department store group this week reporting an 80% profit slump and closure of another three of its stores. Why? Because the operating model of selling fashion has changed. It involves quick turnaround, fresh pieces, 24/7 'trends', online selling platforms, social media branding, and a whole lot of marketing to the right audience. Not to mention aggressive ordering tactics that are downright unethical. Because of this, fast fashion is cheap. Super cheap. As Retail Week Prospect senior analyst Rebecca Marks suggests in June, “The younger consumer wants something they can wear once. They don’t want to be seen on Instagram in the same outfit.” Sad state of affairs, but says it all, really. I don't know if I'm sad or outraged. I suppose the sign of the times is saying that fast fashion has really become Big Fashion (much like its predecessor, Big Agriculture and Big Pharma) and is dominating the retail sector. It's definitely having a moment. It's not the healthiest model for the economy, the planet, and technological pioneering. At the same time, more and more of us are realising that fashion is no longer trendy. As we age, we buy clothes that fit well, last longer and can easily match a few of our wardrobe favourites. We are not swayed by so-called 'trends.' We learn to appreciate sewing, curating our own wardrobe, and the art of mending clothes. With the emergence of alternative fashion brands out there that are providing an ethical consciousness to our current consumer market, there is reason to believe fast fashion will not hold its position and sit on its high horse forever. I'm no economist, but I'd like to believe the insurgence of the slow fashion movement will come to a juncture with the current unsustainable model. It’s highly possible. And it's just a matter of time. Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity. Tags: #conscientiousfashionista #wardrobetruths #lessonsinfashion #ethicalfashion #fastfashion #slowfashion #fashionisnolongertrendy #fashioneducation

|

Details

�

#FashionEducationAdding substance to the Conscious Fashion chatter. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

Resources

Read more.. |

||||||||||||||||

Acknowledgement of Country

FASHINFIDELITY acknowledges First Australian peoples as the Traditional Custodians of this country (known as Australia) and their continued connection to land, sea, and culture. FASHINFIDELITY pays their respects to the resilience and strength of Ancestors and Elders past, present, and emerging and extends that respect to all First Australian peoples. FASHINFIDELITY is brought to you from the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong peoples of the Kulin Nation.

FASHINFIDELITY acknowledges First Australian peoples as the Traditional Custodians of this country (known as Australia) and their continued connection to land, sea, and culture. FASHINFIDELITY pays their respects to the resilience and strength of Ancestors and Elders past, present, and emerging and extends that respect to all First Australian peoples. FASHINFIDELITY is brought to you from the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong peoples of the Kulin Nation.