|

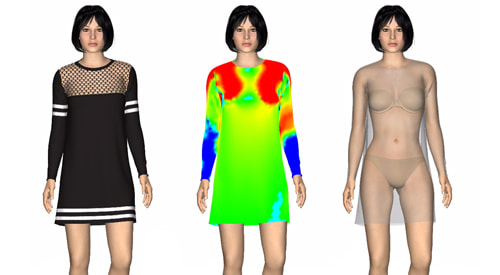

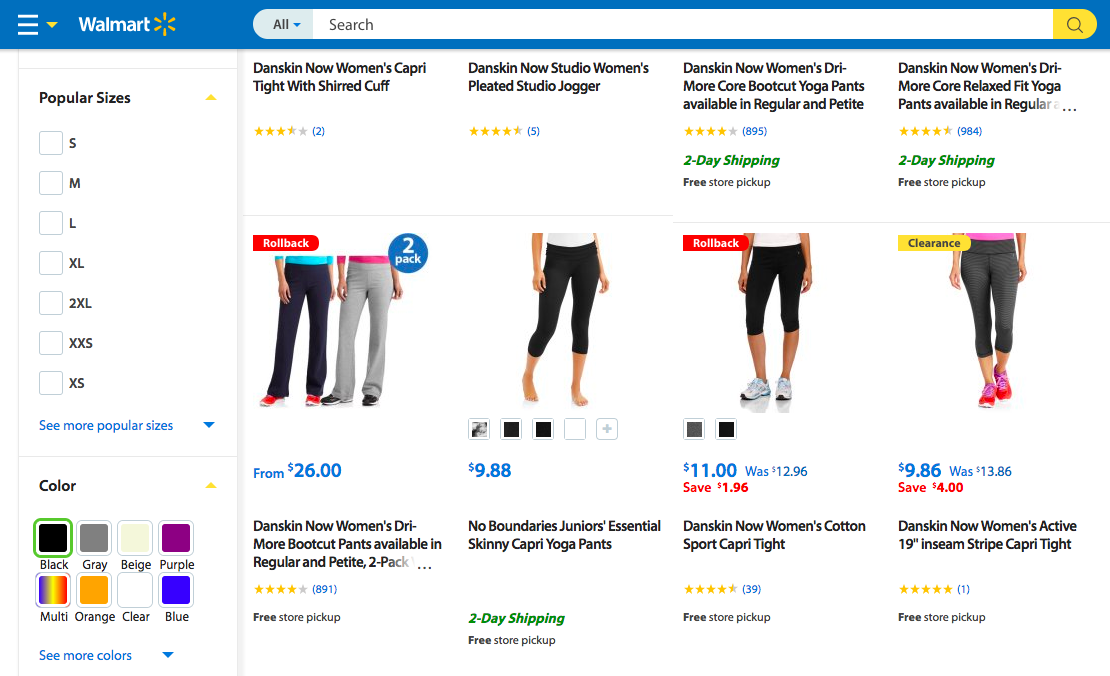

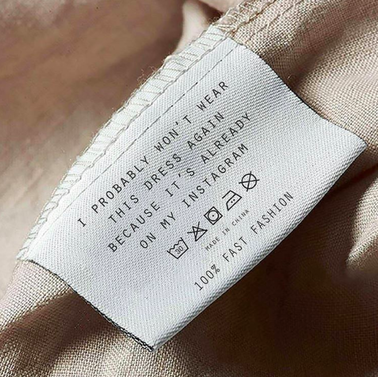

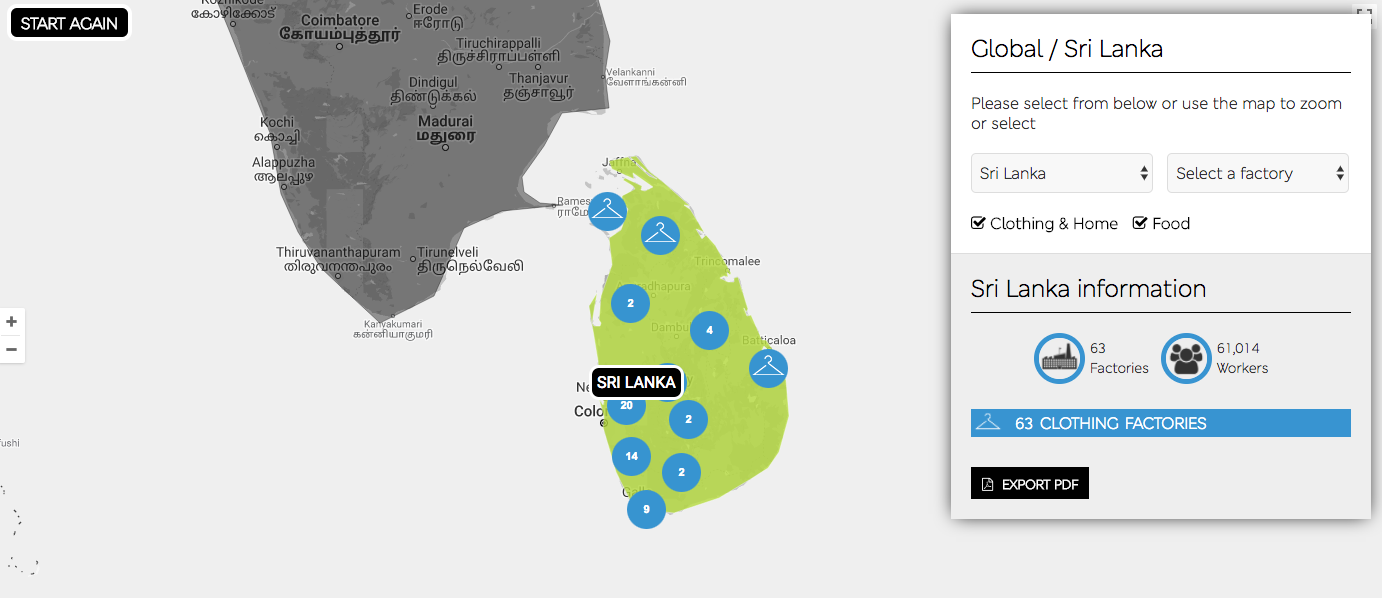

Special Report on the International Conference on the Apparel Industry 2556 words; 13 min read Sri Lanka and Fashion Earlier this month (February 7-9th) I had the privilege of attending the inaugural International Conference on the Apparel Industry, held in Colombo, Sri Lanka. The event was organised by Monash Business School, Monash University, Australia; Joint Apparel Association Forum (JAAF), Sri Lanka; University of Warwick, UK; University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka; Postgraduate Institute of Management (PIM), Sri Lanka, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka; University of Dhaka, Bangladesh; Institute for Manufacturing, Centre for Industrial Sustainability, University of Cambridge, UK; and the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, Sri Lanka. Globally, 60 million people are employed in the apparel or garment industry, with around 15 million employed (largely women) in factories located in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Asian manufacturers supply a very large proportion of the garments sold in developed countries. This year's conference focused on Productivity Improvement, Disruptive Innovation and Leadership. For me, an environmental problem-solving professional who did not have any formal training in fashion, merchandising, apparel making, textiles and fabric creation, pattern making and dyeing, and so forth, I was hoping to meet people in the industry who are. And boy, oh, boy, did I meet them! There's nothing like asking the people who you want to work with how they feel about the idea you are trying to sell. In my case, compulsory environmental footprint labelling on clothes. (More on this later.) And so, on this occasion, the Conference was my first foray into this strange world I'm about to dive into, and how I fit into some parts, if any, of it. Well into the first hour, it's apparent I'm not completely out of place. Even though I am no expert in fashion design, buying textile, or drawing sketches, trying to imagine the way a fabric flows… I am no stranger to manufacturing, where half of my career has been focused on. I am a sucker for process, and I never think about problem-solving without understanding where I belong in the scheme of things. I understand the mechanics of production. And that's something a lot of us in the room had in common. The elephant in the room The Conference's theme did focus on taking your apparel business higher up the value chain. For those who are uninitiated, value chain refers to all the activities, from receipt of raw materials to post-sales support, that together create and increase the value of a product. Reason being: to be competitively advantageous. The phrase "moving up the value chain" essentially means using business processes and resources to produce highly profitable products, also known as higher-margin products. Mr. Riaz Hamidullah, High Commissioner of the People's Republic of Bangladesh to the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, in his keynote speech on Day One, had to remind the Conference attendees that the Apparel Industry has some big structural and governance problems before it can move up the value chain, though. The elephant in the room has everything to do with sustainable consumption, and not just the way we produce clothes in Asia. We weren't able to formally discuss the problem of the current unsustainable consumer habits during the course of the Conference. Nevertheless, he made a great point, and further along in my analysis I'll try to take the elephant out of the room for everyone to notice. For those who've read my posts, you will no doubt already appreciate the fact that I believe the fashion industry is responsible for cleaning this mess up. The elephant in the room has everything to do with sustainable consumption, and not just the way we produce clothes in Asia. Export quality versus 'other' Perhaps ‘moving up the value chain’ resonates more with the export garments market, and very much relevant to Sri Lanka. If this is confusing to you, let me explain. Export market garments generally are made from higher quality materials, fabrics, and prints for the sophisticated consumer. These consumers expect aesthetically pleasing, on-trend clothes that are equally durable and perform well. The export garment industry is Sri Lanka’s primary foreign exchange earner accounting to forty percent of total exports and fifty-two percent of industrial products exports. Sri Lanka prides itself as the ‘ethical’ choice manufacturer of apparel for the export market, and has gone as far as being totally self-regulated, with the mantra ‘Garments Without Guilt’ and corresponding certification being used by the industry to demonstrate responsible business practices and assure international buyers of working conditions in the country. This means, the garments they produce are sold as ‘high-end’ apparel. There’s a reason certain clothing brands claim their products are high-end. Apart from the two biggest costs to producing clothes – the manufacturer and the fabric – there’s the cost of compliance. Substance regulations, labelling requirements, documentation requirements, and lab testing requirements all vary by import country. One of the more important factors to consider is the not-so-cheap costs of making compliance requirements happen. Clothing textiles are regulated in most countries, including the United States, Europe and Australia. Most applicable safety standards, such as REACH (Europe) and FHSA (United States) regulate substances, such as formaldehyde, AZO-colours and asbestos. Now let’s look at the industry in general. Most Chinese manufacturers, especially the smaller ones, are not aware of the substance content in their textiles. (China is the biggest clothing manufacturer in the world, by the way.) According to this source, it’s a deeply rooted issue that goes way beyond the manufacturer. All clothing manufacturers purchase fabrics and components from subcontractors. The number of subcontractors can range from a two or three, to more than one hundred. Apart from the two biggest costs to producing clothes – the manufacturer and the fabric – there’s the cost of compliance. The best reflection of compliance to standards is the price of the product. Take, for example, lululemon Athletica, the Canadian athletics apparel retailer. A pair of their best-selling three-quarter yoga tights retail for US $128.00. I know for a fact that they are manufactured at MAS Holding’s Shadowline factory in Katunayake, a highly efficient and lean factory that I had the privilege to visit on the last day of the Conference. The price of the lululemon tights, compared to a US $10.00 similar pair from Walmart, paints a story of two worlds. Yes, those yoga tights may be compliant to USA regulations for imports to be sold at Walmart stores. But it still raises questions, doesn’t it? Additionally, does it make sense now that clothes made for the Asian market, for example, are of inferior quality? Lower-income households in Asia have always only bought clothes that they needed, due to their restricted budget. Whether or not these garments are of high quality, is not the issue. Fast fashion caters for those who have disposable income and encourages unnecessary spending on stuff you don’t actually need. The apparel manufacturing market for the locals may not cater for discerning first world tastes, but that is because they value function and their wages, more so than aesthetics. Perhaps, even, making sure they have enough food to eat and that their children go to school is more of a priority than buying on-trend clothes. Are manufacturers ready for digitisation? Professor Amrik Sohal, in his opening presentation, mused about how they started on this journey. About four years ago when Monash Business School was looking at the challenges of this industry, they made a concerted effort to analyse Bangladesh’s Ready Made Garments (RMG) industry as a case study. Discussions were held with factory owners, garment merchandisers, as well as governmental departments and management professionals in positions of influence. After much analysis, they presented their findings to the country’s top officials and a national forum was held. In summary, Bangladesh sat on the lower spectrum of the industry in terms of supply chain value. As a whole, the industry is still reliant on local and overseas business for quantity of products delivered, as opposed to quality, due to its relatively cheap labour costs. When I was in Katunayake, I didn’t feel like I was in an unindustrialised nation. So when we start discussing value chain and product edge, Sri Lanka has embraced this, as evidenced by the factory visits I attended as part of the Conference. The three facilities I visited are all situated in Katunayake, an industrial estate a stone throw's away from the capital city's airport: MAS Holdings’ Shadowline factory, which specialises in making fitness and activewear garments, Hirdaramani’s factory that specialises in knitted garments and children’s clothing, and STAR Garments' Innovation Center that focuses on STAR’s digital expertise to produce prints, samples, and pattern making, among others. The Innovation Centre was officially opened in October 2017 and is the first passive house designed in South East Asia. (In Europe, passive houses are designed to keep warmth in, but in this case, keeping conditions cool.) When I was in Katunayake, I didn’t feel like I was in an unindustrialised nation. These factories are heavily audited to international manufacturing and quality standards, are fully compliant with their regulatory licences, and most importantly, values their people. Keeping in mind that Sri Lanka Apparel is a signatory to 41 of the total number of conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO), and the only country with a significant manufacturing industry to do so, they have to look beyond cheap labour to provide value, and are well on their way in implementing productivity improvements and innovation. It was clear to me that MAS Holdings, for example, has fully applied vertical integration in their supply chain to deliver short lead times to provide value to their buyers. One of the challenges of the apparel industry is undoubtedly the laborious aspects of assembling clothes. (I shall reserve my commentary on the textile production side of the industry for now, as the conference did not touch on this.) It seems to me that in most parts of the industry in this region, the churning of the quantities in lighting speed time and at the cheapest possible cost – is still the preferred way to do business. After the panel discussions and the factory visits, it’s obvious that the industry as a whole in Asia, even though within close geographical proximities to one another, has a long journey ahead in embracing value-added, high-end manufacturing of products. ....the churning of the quantities in lighting speed time and at the cheapest possible cost – is still the preferred way to do business. The other apparel-making countries; notably China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, India, Hong Kong, Turkey, and Indonesia – how can they prepare themselves for Industry 4.0, when the basics of safety, transparency, and compliance is still problematic? Fast Fashion still responsible Well, they may not be ready. But that’s not entirely their fault. The disruptors in the apparel industry have perfected the fast fashion retail model, where trends are created based on what’s going on the street, ditching the two-season cycle of sales altogether. These brands know what it takes to successfully set up fashion retail operations with omnichannels, they have considered imports and exports across regions, and they have a scientific inkling on measuring supply and demand. Manufacturers of garments in Asia didn’t really get a chance to have a say in the way fast fashion works: they just had to bear the grunt of the demands placed on them. It kind of happened really quickly, and the Asian factories were only eager to be part of it. The big brand players placed heavy emphasis on the manufacturers that fashion retailing had changed; that this is the new world order; and if you did not meet demand, then you’re not going to reap the benefits. It’s a revolution of a treacherous kind, though. If the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh didn’t teach us anything, then what can? The societal and environmental impacts in delivering these ‘fashionable’ pieces are much too great. Compliance to safety standards is one thing, but as Professor Jan Godsell, from Warwick Manufacturing Group, UK, said in her keynote address at the Conference, “...the current model of economic development is broken. We can’t have economists measure the success of businesses by how much they sell products that consumers don’t actually need.” This is the elephant in the room problem Mr. Hamidullah mentioned on Day One. It’s been almost five years since that fateful day in April, and the international brands that manufacture in Bangladesh are still nowhere near cleaning up their act in terms of improving fire and building protocols and being accountable for their supply chain. A December 2015 report, written by the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, found that only eight of 3,425 factories inspected had "remedied violations enough to pass a final inspection" despite the international community's $280 million commitment to clean up Bangladesh's RMG industry. Sarah Labowitz, the co-author of the 2015 NYU study, sees the flaws in the efforts to remediate Bangladesh’s factories. “[The unfinished remediation] also demonstrates the limits of the model where you basically push all the responsibility and the blame onto factories. There needs to be more accountability for the brands themselves… In some ways, the Accord and the Alliance, they’re the most intense version of a strategy that's been tried for 25 years to try and reform bad factories. And it’s just not working.” The power play As we stand today, the apparel industry in Asia may well be just that one step behind in trend setting, but they know how production works. One of the more prominent debates coming out of the Conference was the fact that the regional manufacturers’ supply chain linkages are strong. This is the kind of knowledge that the buyers and fashion houses, headquartered in Europe, USA, or Australia are far removed from. Monash University has been looking into this as part of their research into sustainability in apparel manufacturing, and thinks this makes for a compelling case of reversing the demand power balance. "....We can’t have economists measure the success of businesses by how much they sell products that consumers don’t actually need." This journey counts After some heartening and equally disheartening conversations in Sri Lanka over the course of three days, I remain optimistic. I was in bed with good company. If anything, Sri Lanka has shown the conference delegates how the foundations of sustainability can be erected. I can only hope that the appetite for making quality garments continue within the region, and that consumers and manufacturers keep demanding safer, and fairer practices for themselves – this is the real ‘trend’ that is going to shape the apparel industry. In parallel, advocates and governments can push the agenda of regulation, too. This disruption and innovation journey is so important. Sri Lanka is only the beginning. Our conversations today will pave the way for the right leadership to move ahead with confidence and competence. To close, I quote Professor Godsell, “We can be a part of the changing trends, not a victim of it.” The future looks bright from here. Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtag #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity. Tags: #conscientiousfashionista #fastfashion #slowfashion #ethicalfashion #wardrobetruths #fashioneducation #fashionisnolongertrendy #digitisation #SriLanka #apparel #textile #clothing #passivehouse #srilankanapparel Useful links:

Please note I was not paid to go to the Conference, and all expenses of the trip was beared wholly by me.

5 Comments

11/4/2024 04:00:24

Thanks for your post.cube Star International Ltd.is a Global Trade Navigator.We simplify import and export.

Reply

1/5/2024 22:09:51

Thanks for your post.cube Star International Ltd.is a Global Trade Navigator.We simplify import and export.

Reply

1/5/2024 23:57:27

Reply

4/5/2024 14:08:26

Thanks for your post.cube Star International Ltd.is a Global Trade Navigator.We simplify import and export.

Reply

8/5/2024 00:04:55

Thanks for your post.cube Star International Ltd.is a Global Trade Navigator.We simplify import and export.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

�

#FashionEducationAdding substance to the Conscious Fashion chatter. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

Resources

Read more.. |

||||||||||||

Acknowledgement of Country

FASHINFIDELITY acknowledges First Australian peoples as the Traditional Custodians of this country (known as Australia) and their continued connection to land, sea, and culture. FASHINFIDELITY pays their respects to the resilience and strength of Ancestors and Elders past, present, and emerging and extends that respect to all First Australian peoples. FASHINFIDELITY is brought to you from the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong peoples of the Kulin Nation.

FASHINFIDELITY acknowledges First Australian peoples as the Traditional Custodians of this country (known as Australia) and their continued connection to land, sea, and culture. FASHINFIDELITY pays their respects to the resilience and strength of Ancestors and Elders past, present, and emerging and extends that respect to all First Australian peoples. FASHINFIDELITY is brought to you from the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong peoples of the Kulin Nation.